Rethinking Homework to Focus on Fluency

Data reveals that eliminating traditional assignments supports educational equity.

Topics: Equity and Diversity

Do a quick search of “homework at the elementary level,” and Google will present up to 75 million articles either denouncing it or listing its potential benefits. I, too, have been of many minds on the topic; during 25 years in education, my opinion regarding homework’s value has changed at least 25 times.

There was only one way for me to find out if my school could maintain academic excellence without homework. During the 2019–2020 school year, I challenged the school staff and families to complete some action research with me by implementing a “No-Homework November and December.”

This was a scary concept for some members of the school community. Our district has a long and storied tradition of academic excellence. My argument? What made us successful in the past won’t necessarily make us successful in the future.

The first step of this adventure was to educate parents and students on what I meant by “no homework.” While the staff and I question the value of spelling lists and worksheets completed at home, we wholeheartedly believe in the value of practicing math facts regularly, as well as reading to and with children. We continued to communicate that fluency is key to academic performance.

Fluency refers to a student’s ability to read and recall accurately, quickly, and effortlessly. We sent the message that reading and math fact fluency are the building blocks of comprehension and high-level thought. Families were encouraged to practice math facts and read daily for 15 minutes. The hope was that families would use the extra no-homework time to start new, fun routines with their children.

Participation Spikes

After the two-month no-homework trial, we surveyed parents and teachers. The surveys had some of the highest participation rates compared to previous surveys, and the feedback was mostly favorable. Accountability and communication were the main concerns of teachers and families.

We analyzed December benchmark data, comparing the results to those of previous years. Quantitative data proved tricky to review due to a districtwide change in benchmarking companies from the previous year. From September to December, fourth- and fifth-graders showed greater growth in math than in reading on districtwide benchmark assessments—growth comparable to that of our sister school.

I ultimately made the decision to move forward with the shift from traditional homework toward practices focused on fluency. I made several modifications to how the school implemented the change. We changed our vocabulary; we stopped saying “no homework” and instead talked about “fluency practice.” Teachers were given the option of assigning fluency practice logs, which parents appreciated because it made practice and accountability into requirements.

We learned that parents value homework because they feel it helps them understand the skills and concepts students are studying and learning. The staff and I used a January faculty meeting to brainstorm ways other than homework to improve our communication with families.

Five Months Later

I enjoy analyzing data; it’s what helps me help my staff make their “good” better and their “better” best. But due to COVID-19’s school closings, I didn’t have year-end school benchmark or state achievement data to analyze. I wouldn’t be able to compare and contrast the academic data from the days when we assigned traditional homework against that of our fluency-focused student cohort.

The data I did have available is school discipline data. And what I uncovered is astonishing!

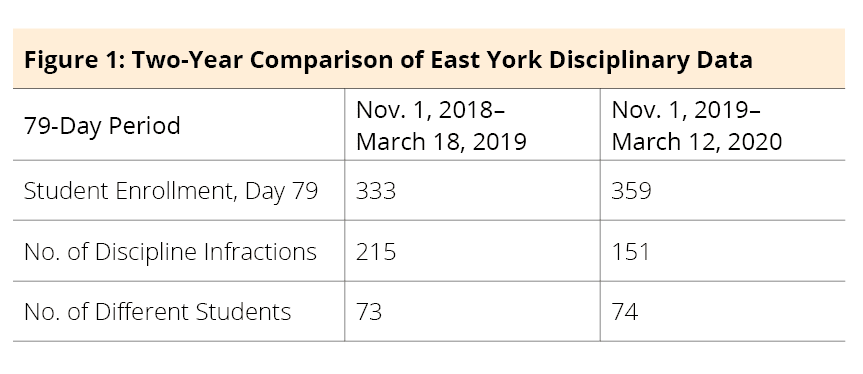

From Nov. 1, 2019, through our final in-person day on March 12, 2020, there were 79 days of school. I narrowed the 2018–2019 data to a comparable 79 days of school. As I expected, there were fewer disciplinary infractions for failing to complete homework. But even though there were 26 more students in the building in 2019–2020, there were 64 fewer discipline infractions reported to the office than in 2018–2019.

Things became even more interesting when I looked at discipline through the lens of race and ethnicity. (See Figure 1 below)

I had never seen anything like this. On March 12, 2020, the racial and ethnic breakdown of the student body at East York Elementary School was 67 percent white and 33 percent minority. So 65 percent of the discipline assigned while performing fluency-focused action research went to white students, and 35 percent to minority students—roughly matching our school makeup for the first time.

Is it possible that when we make homework attainable for all students, regardless of their home supports, we improve the school environment? Is it possible that when we remove homework variables that are beyond our students’ control, they feel more confident at school? Is it possible that when we make bold choices in instruction, we make all learners feel like valued members of our school community?

These things are possible. At the very least, East York Elementary seems to have uncovered a truth about traditional homework: It favors nonminority students. Concentrating on fluency instead improved the school climate.

Denise R. Fuhrman is principal of East York Elementary School in York, Pennsylvania.