Putting Restorative Practices to Work

Providing PD isn’t enough to realize the benefits of restorative practices.

Topics: School Culture and Climate

For centuries, schools have relied on exclusionary discipline approaches such as suspensions and expulsions to deter and limit misbehavior and the harm that can result. Research from the fields of psychology, sociology, and economics, however, consistently indicates that when students are excluded, it increases incidences of misbehavior as well as detachment, mental health challenges, dropout rates, and juvenile and adult incarceration.

Moreover, because exclusionary discipline is often applied unevenly (with, for example, Black students being more likely to be excluded than their white peers for similar behaviors), reliance on exclusionary approaches might exacerbate equity issues and make it harder for schools to serve the educational needs of all students. What can schools do when students are in conflict or break school rules?

Many schools have adopted restorative practices in order to strengthen social structures, encourage prosocial behaviors, and mend relationships when conflict occurs—without excluding students from school. There are two main categories of restorative practices:

- Community-building practices. Such practices are designed to foster an interconnected school community and a healthy school climate; a good example is community-building circles that help students and staff deepen interpersonal relationships.

- Repair practices. These practices attempt to bring together all stakeholders to resolve issues and take productive steps in the future and include conflict-responsive dialogues, mediation, and harm-repair circles.

Restorative practices sound good on paper, but as any principal who has tried to implement them can attest, making the transition from providing professional development (PD) in restorative practices to realizing their widespread use can be challenging. This has implications for educators who want to measure the effect of restorative practices and realize the kinds of impacts such practices are designed to achieve.

Measuring Implementation

Recently, some researchers have shifted their approaches to the measurement of the impact of restorative practices to avoid the assumption that PD automatically leads to practice utilization. Instead of judging restorative practices by tracking the performance of schools that get PD, these researchers reviewed the experiences of students who actually get exposure to restorative practices.

It’s the same with any offered resource. Let’s say you’d like to know if eating healthy lunches improves students’ focus during afternoon classes. You could look at schools with certain nutrition programming and evaluate how students in those schools are performing academically, and under the ideal conditions, this approach would work. But if students aren’t taking advantage of nutrition resources, you won’t be able to understand if nutrition makes a difference. The story would be different if you could track which students take advantage of the nutritious offerings and see if those students see improvements in focus and academic performance. In short, to make an accurate assessment of any initiative, you must focus on what students actually get. That’s why some researchers have asked in recent studies what happens when students actually gain exposure to restorative practices—and their results have been profound.

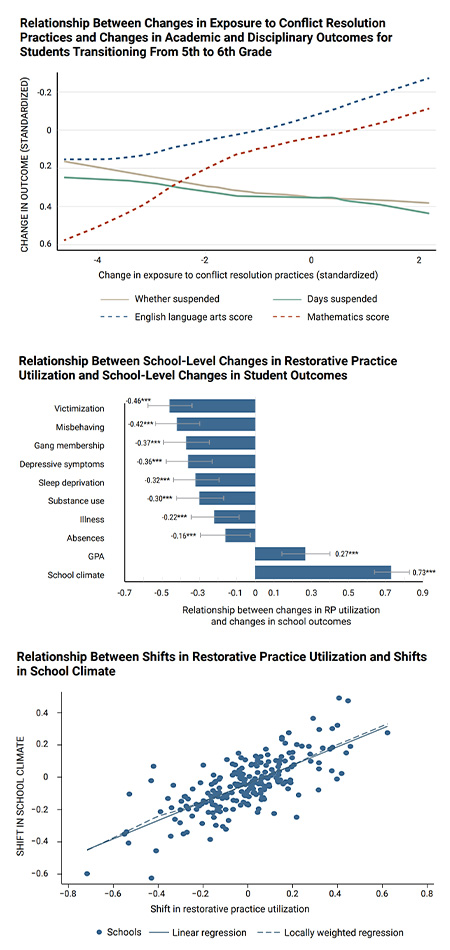

One study from the Learning Policy Institute (LPI) followed more than 34,000 students in California who switched schools between the fifth and sixth grades, finding that students who were exposed to increased usage of restorative practices benefited from marked declines in suspension rates and numbers of days of suspension. At the same time, they saw strong increases in performance on standardized tests of English and math.

While students of all backgrounds benefited from exposure to restorative practices, the results were particularly strong among Black and Hispanic students. This suggests that increasing exposure to restorative discipline could help reduce Black-white and Hispanic-white gaps in discipline and academic achievement.

The study suggests that when students switch to a more restorative school, they benefit. But what happens when a school grows more restorative over time? The study also followed 220 schools and tracked student experiences with restorative practices over a six-year period, finding that schools in which students reported more exposure to restorative practices saw a range of improvements, including:

- Reductions in misbehavior, victimization, gang membership, and substance use;

- Improvements in student health, including decreases in depression, sleep deprivation, and illness;

- Improvements in educational outcomes, including reduced absence rates and improved grade-point averages; and

- Marked increases in student climate.

These findings point to the potential of increasing students’ exposure to restorative practices, but it’s easy to overlook the fact that the LPI analysis also examined what happens when a negative change occurs in student exposure. When students saw declines in exposure to restorative practices in schools, outcomes generally got worse, particularly in assessments of school climate.

Guaranteeing Exposure

These results suggest that increasing student exposure can help improve student behavior and performance, reduce racial disparities, and ultimately lead to schools that are safer, healthier, and more connected. But they also beg another question: How can schools increase student exposure to restorative practices? Simply providing professional development is not enough.

The LPI report recommends several steps for principals to take if they are hoping to embark upon a journey toward a restorative community or enhance the efforts they have already made:

Shift from a culture of exclusion to a relational culture. Research indicates that schools where administrators, staff, and students hold belief systems that align with restorative practices often have better experiences in implementing such practices. In other words, principals must commit to cultural transformation to realize restorative practices’ intended impacts.

This requires spreading awareness that punishment can be harmful and might cause misbehavior; helping staff recognize that relational approaches can improve behavior; and abandoning practices that are incompatible with restorative practices, such as zero-tolerance policies in which exclusionary discipline must be applied whenever students engage in specific conduct.

Schools with school resource officers (SROs) must include SROs in the cultural transformation. Typically, research has found that schools with more SROs use more exclusionary practices and offer poor school climates for members of groups who experience exclusionary discipline at higher rates. Training for SROs could help empower them to be part of restorative cultural transformations in their schools.

Develop staff mastery. Part of the reason PD alone can fail to advance student exposure to restorative practices is that staff often experience hesitation or challenges in understanding, adopting, and adapting the techniques.

Some of the more successful implementations of restorative practices have occurred when teachers opted in to PD rather than being forced. This may be because staff who opt in believe in the value of restorative practices and are better positioned to learn and adopt them. Securing staff buy-in for PD before it begins may be key. Principals can achieve this through open, honest conversations about the harms of exclusionary discipline and the potential benefits of restorative approaches.

To facilitate adoption and adaptation of restorative practices, principals can provide teachers with coaching, ongoing professional development, and opportunities to join professional learning communities that focus on deepening teachers’ abilities to implement these practices.

Ensure that students of all backgrounds gain access to restorative practices. While the LPI report indicates that restorative practices can be particularly beneficial to Black students, it also suggests that students from certain backgrounds (particularly Black and low-income students) experience less exposure to restorative practices than their peers.

Principals can take steps to ensure that teachers use restorative practices when interacting with students of all backgrounds by providing PD designed to help teachers form deep connections and positive relationships with students of all backgrounds.

Empower sustained implementation. In some studies of restorative implementation, trend lines in outcomes (such as academic performance) over time are U-shaped, meaning there are short-term declines followed by long-term gains.

Principals hoping to realize the positive impacts of restorative practices might want to structure implementation to be sustained for multiple years in order to “ride out” the growing pains of the shift to a new culture and approach to discipline. It takes time to accrue the benefits of a restorative community.

Current research says that when restorative practices are supported by a cultural shift that makes PD more than theoretical, student performance and equity see marked improvements alongside decreases in exclusionary discipline. Let’s all strive to put such practices in place for the benefit of all children.

Sean Darling-Hammond is an assistant professor in Public Health & Education at the University of California, Los Angeles.