6 Secrets to Implementing Change

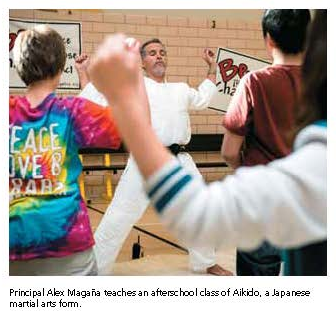

Communicator October 2014, Volume 38, Issue 2 The September/October issue of Principal magazine explores how principals can manage change—from shifting demographics, to new standards and federal guidelines. In this excerpt from “Change, Setbacks, and Transformation,” Denver principal Alex Magaña (pictured below) shares the story of how his school became an “innovation school,” and the lessons he learned along the way.

Communicator

October 2014, Volume 38, Issue 2

The September/October issue of Principal magazine explores how principals can manage change—from shifting demographics, to new standards and federal guidelines.

In this excerpt from “Change, Setbacks, and Transformation,” Denver principal Alex Magaña (pictured below) shares the story of how his school became an “innovation school,” and the lessons he learned along the way.

I became principal of a struggling Grant Beacon Middle School in Denver midway through the 2010 school year after our principal was promoted. It was difficult to discern the right moment for change: If I moved too quickly, I would fail, and if I moved too fast, I was destined to lose teachers and students along the way.

I became principal of a struggling Grant Beacon Middle School in Denver midway through the 2010 school year after our principal was promoted. It was difficult to discern the right moment for change: If I moved too quickly, I would fail, and if I moved too fast, I was destined to lose teachers and students along the way.

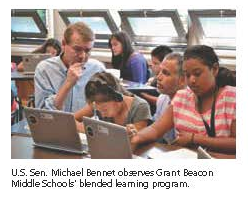

To become a blended learning school, we dismantled our computer labs and set up systems to support our blended learning model. We did this in stages, starting with just reading and math classrooms at first. It was important not only to rely on outside resources, but also to look at the resources that existed within our building.

We also committed to extending our school day to provide our students enriching activities, interventions, and advanced classes aligned with our academic goals. To make this happen, our staff collaborated to create a schedule that worked for everyone while adding five hours of instructional time to our week. Teachers received a small stipend for the added time. Community members also were invited to share their expertise by leading enrichment courses. For example, one parent convinced her employer to let her teach an aerospace engineering class. Now, we have rockets launching in our playground and kids learning how to fly.

Another upside for teachers was that by partnering with parents and community providers to lead enrichment activities, we could carve out more time for teachers to plan, collaborate, and develop lessons.

Today, Grant Beacon is thriving. Our more than 50 enrichment programs often are led by outside partners, including business experts, Shakespeare drama troupes, and local scientists. We now have a waiting list to get in. We have shed our low performer status and erased “failure” from our vocabulary.

Lessons Learned

Here are six strategies that we have determined are essential to thriving when implementing a change initiative.

1. Create a sense of urgency. Only 10 percent of our students would stay after school to take advantage of extra help we offered. I often had to pull them off buses for not completing homework. As a principal, you have to analyze your data and have an idea of where you want to take the school. This cannot be done alone; it has to be done with a team.

2. Build your team. People want to help when the cause is right and the problem is defined. My dean of students found community providers that normally teach after-school programs to teach during our extended day time and help make our new schedule work.

3. Don’t be afraid to ask for help. We knew that it would take a team effort to make the needed changes. I spoke to everyone from teachers, parents, community members, and board members to the superintendent to get the help needed for our school. Sometimes they would decline joining a team or committee, but instead give valuable advice, and other times they would just point me in the right direction to get what we needed.

4. Develop a shared vision. Don’t underestimate the importance of defining what you are trying to solve or become. We often skip this step, which allows an effort to go in different directions. Today, our mission statement is the mantra that guides decisions and keeps us on track.

5. Never let up. Setbacks are part of change. There were plenty of times where I questioned the direction and my own leadership skills, but we still continue to move forward. When times get tough, I remind my staff and parent leaders that our mission is to uphold Grant Beacon’s shared vision for how to best serve our students.

6. Celebrate success. We are approaching our third year of focusing on blended learning and our extended school day. In one year, we went from not meeting to meeting expectations. We have also increased the demand for our school. For the first time in our school’s history, we have a waiting list of students asking to attend. Our attendance has improved by 2 percent, and we have even reduced our out-of-school suspension rate by more than 50 percent.

Read Magaña’s full article.

—

Copyright © 2014. National Association of Elementary School Principals. No part of the articles in NAESP magazines, newsletters, or website may be reproduced in any medium without the permission of the National Association of Elementary School Principals. For more information, view NAESP’s reprint policy