What’s My Role? – Part 1

Principals share their leadership responsibilities with APs according to district demands, school needs, career goals, and personal strengths.

Topics: Assistant Principals

Assistant principals and principals share the same basic set of tasks—so much so that their job descriptions often look very much alike. The exact distribution of responsibilities varies from school to school and team to team, but whether it is administration, discipline, or instructional leadership, the AP’s role largely fills in the blanks designated by the school principal.

According to an April 2021 report, “The Role of Assistant Principals: Evidence and Insights for Advancing School Leadership,” from Vanderbilt University and Mathematica, commissioned by The Wallace Foundation, principals are key to determining the scope of their assistant principals’ roles. And what they base those decisions upon often has less to do with state and district policies than the school’s needs and APs’ observed strengths.

“The principal has a huge task—ensuring student achievement—and everything falls on his or her shoulders,” says Jerod Phillips, assistant principal of Cedar Lane Elementary School and NAESP’s 2021 National Outstanding Assistant Principal for Delaware. “That said, the AP [is] learning all aspects of the building so that at any given moment, he or she can pivot to address anything that can take significant time away from the principal being a true instructional leader.”

Setting a Standard

Most states and districts don’t have distinct professional standards for assistant principals and principals. Even the districts that participated in The Wallace Foundation’s Principal Pipeline Initiative (PPI) rarely distinguished between the responsibilities of the two roles, the report says, sometimes failing to define professional standards for assistant principals at all. The lack of definition likely makes it more difficult to prepare APs to move into the principalship.

In eight Tennessee school districts surveyed during the 2017–2018 school year, the primary difference between assistant principals’ and principals’ job descriptions is that assistant principals’ job descriptions usually note the obvious: They will “assist,” “help,” “work jointly with,” and otherwise “support” principals on various tasks.

“The assistant principal is responsible for supporting the principal in conducting all academic programs, as well as the business and daily operations of the school,” says the Knox County (Tennessee) Schools manual. “The assistant principal may serve as the principal designee in [the principal’s] absence. The assistant principal reports to the appropriate principal as assigned.”

The principal, the document indicates, “will serve as the instructional leader of the school”; “supervise all professional, paraprofessional, administrative, and nonprofessional personnel”; and “facilitate, with all school stakeholders, the creation and implementation of a shared vision of excellence for every student.”

In a building, however, the reality is more nuanced. Assistant principal “Aqila [Malpass] is not so much supporting me as she is co-leading the school,” says Dilhani J. Uswatte, principal of Rocky Ridge Elementary School in Hoover, Alabama, and an NAESP National Distinguished Principal (NDP) for 2020. “I see her as a partner, not as someone who serves me.”

Regarding the Responsibilities

The responsibilities of assistant principals and principals alike fall into in three main domains—administration (supervision, evaluation, planning, budgeting, training, etc.); student discipline (enforcement, attendance, counseling); and instructional leadership (curriculum selection, observation and evaluation of teaching, professional development).

Traditionally, APs have been charged with discipline and spent the majority of their time on related tasks, while the principal concentrated on instructional leadership and administration. But the more recent the study, the Vanderbilt and Mathematica researchers found, the more varied the APs’ tasks were. Today’s assistant principals are more likely to dabble in all aspects of school operations, including instructional leadership.

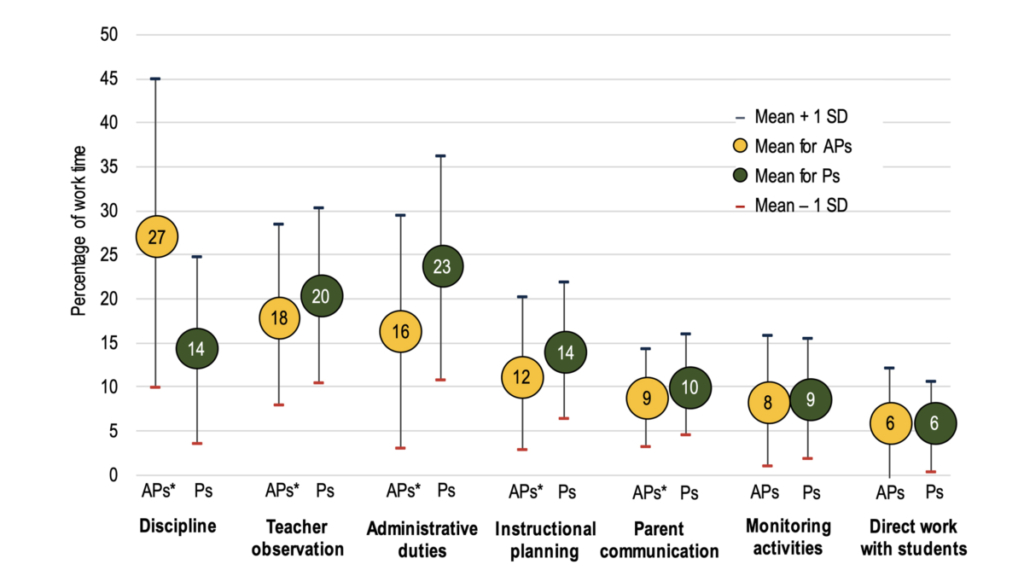

Distribution of Labor for Assistant Principals (Source: Tennessee Educator Survey Data from Tennessee Department of Education, 2017-2018)

The roles “are based upon school system norms and requirements,” says Edward C. Cosentino, principal of Clemens Crossing Elementary School in Columbia, Maryland, and a 2019 NAESP NDP. “For example, the principal is not permitted to be the school accountability coordinator [in charge of testing], so that falls on the assistant principal.”

Once they have the basics covered, an AP might choose to take on new responsibilities. “We follow school system requirements,” says Clemens Crossing AP Sonia Hurd. “If there is an additional task I would like to take on, I can work with the principal to determine the next steps.”

Straining to Meet Standards

Stricter state standards might be contributing to the expansion of APs’ purview, the report says. With many principals straining to meet state teacher evaluation mandates and the current trend toward distributed leadership, more principals might be offloading some aspects of their instructional leadership burden to their assistant principals, such as performing observations and providing feedback to teachers.

Malpass, 2021’s National Outstanding Assistant Principal for Alabama, has taken on more instructional leadership responsibilities than the traditional AP, spending 60 percent of her time on such tasks. “There has to be a focus on curriculum and instruction, and I can’t dedicate 100 percent of my attention to that,” Uswatte says. “That is a great responsibility, and I want Aqila to wear that hat.

“When one of us is out or we’re facing a difficult situation, there will be overlap,” Uswatte adds. “We both touch everything. [On] instructional leadership needs, we might talk about it, but Aqila will run with it. Or I might be in charge of a discipline situation, but Ms. Malpass has incredible relationships with some students, so it would be foolish of me to say ‘No, don’t do that—I’m in charge of discipline.’ ”

Preparation or Profession?

According to research studies cited in the report, the historical tendency to limit exposure to instructional leadership tasks might undercut APs’ preparation for the principalship, “given that instructional leadership is a key responsibility of effective principals.” Although most assistant principals express satisfaction with their roles, the researchers add, most appreciate the opportunity to grow.

“This depends on the leadership style of the principal,” Phillips says. “The roles assigned to the AP should be good preparation for the principalship if they involve instructional leadership tasks—including PD—that transcend discipline issues and lunch duties.”

Few official job descriptions portray the assistant principal position as one that prepares a person for the principalship, however. A district in Pennsylvania mentions that the assistant principal role might be seen as a likely “stepping stone” to the principalship or a career position in and of itself. Similarly, principals’ job descriptions don’t demand that they mentor or prepare their APs to move up.

“We want to make it a stepping stone,” Uswatte says. “To me, the whole point is to make sure Ms. Malpass is ready to take on the responsibilities as principal.”

“A lot of times, Dr. Uswatte will say, ‘This is for when you are a principal,’ ” Malpass adds. “She makes it clear that she is giving pointed advice and wisdom.”

Two Tracks for Leadership

At Clemens Crossing, different rules apply when the AP wants to move up eventually. “If the AP is interested in being a principal, the jobs are not much different,” Cosentino says. “In that case, I call the AP a principal-in-training, [and there is] more overlap. If the AP is content with being an AP and not a principal, the responsibilities tend to be divided more.”

Hurd prefers to operate as a

principal-in-training and spends about 60 percent of her time on discipline, 30 percent on instructional leadership, and 10 percent on management/administration. Roughly the inverse of the principal’s, her task mix combines “district requirements, the interests of the AP, and the skills necessary to become a principal,” Cosentino says.

The decision depends on the individual in the role. “It can be a stepping stone in the sense of learning from a seasoned principal while growing your leadership capacity,” Phillips says. “It can be a career position for someone who enjoys leading and working alongside someone but [doesn’t] necessarily [want] to have every aspect of a school fall on his or her shoulders.”

Playing to Strengths

Leadership tasks at Cedar Lane are divvied up at the building level by Phillips and principal Gina Robinson. “My principal has always involved me in deciding how tasks would be divided up,” Phillips says. “She looks at each of our strengths and the areas we both wanted to work on as factors.” He adds that he can spend the majority of his time on instructional leadership, thanks to the positive climate and culture Robinson has created.

“[It] is based on perceived strengths and school needs—the most efficient way to ensure that skill sets are maximized,” Phillips says. “There is a lot of overlap, and that helps build and maintain the principal/AP relationship, which makes the team stronger. The overlap forces the principal and AP to collaborate, strategize, and talk things through.”

“The most important thing is to take into consideration the gifts and attributes of the person you’re working with,” Uswatte says. “It became apparent quickly that [Aqila] could handle many things, so I encouraged her to do many things. We wear certain hats officially but do a mixture of each other’s jobs.”

Everyone should be permitted to evolve in their role, Uswatte adds. “I have learned to understand what the gifts of each of the people [I] work with are and [to] amplify them. When you have someone you see as a partner as an assistant principal, the faculty, staff, and students can see that. It’s like a good marriage—that chemistry is essential for running a great school.”

“I’d love to see more principals operate in the way Dr. Uswatte does,” Malpass adds. “With other assistant principals, I just feel bad for them because they don’t have the ability to touch all areas of their schools; [it] really is a prime growth opportunity. So many assistant principals get put in a box, instead of someone recognizing where they can have a greater impact.”

Ian P. Murphy is senior editor of Principal magazine.