Offer Corrective Feedback With Empathy

Clarify expectations and define what excellence looks like for teachers needing to improve their performance.

Topics: Mentoring and Coaching, Teacher Effectiveness

Principal Jackson was practically in tears. She admired the teacher to whom she was talking; she was one of the best in the school. Now, Principal Jackson had to call the teacher out. How could she deliver corrective feedback while communicating her respect and support at the same time?

A primary job of every school leader—experienced or novice—is to develop teachers who can support student success. Feedback conversations regarding performance are a big part of that. The Wallace Foundation’s 2021 research synthesis, How Principals Affect Students and Schools, by Jason A. Grissom, Anna J. Egalite, and Constance A. Lindsay, says that principals who excel at providing impactful feedback can increase teacher effectiveness up to 20 percent over time. But most principals have received little training on ways to deliver feedback effectively.

Over the past 12 years, members of the Pitt County (North Carolina) Schools team have been able to access training from some of the world’s best leadership development, coaching, and feedback organizations with the help of grants totaling $25 million. Through that training, we focused on developing school and teacher leaders by applying structures to coach, collaborate, and implement continuous improvement processes. We developed the “TALK” protocol to support principals in effectively communicating corrective feedback toward identified goals.

Start With a Mindset

Providing impactful feedback begins with the right mindset. The way in which we approach a conversation has a direct correlation to the ways in which we engage in it.

A common struggle we found among principals is creating a balance between high expectations and caring for individuals. Overemphasize expectations, and you’re likely to achieve short-term results but build a poor professional culture; overemphasize care, and you might see low accountability and a culture of mediocrity. To support teacher success, leaders must clarify what excellence means and provide empathy at the same time.

School leaders found success when they were able to resolve the tensions between exceeding expectations and guaranteeing an acceptable standard.

A principal and teacher prioritize a few critical steps to help teachers focus on exceeding expectations on those critical steps, while maintaining acceptable standards on minor tasks.

The way in which leaders clarify excellence is important. When they do so without empathy, people might feel like cogs in a wheel. But when leaders provide empathy while clarifying excellence, they treat teachers as respected professionals.

To empathize with teachers, principals need to invest the energy necessary to understand their motivations, hopes, and fears and give them the respect and dignity they deserve. Empathy exercised in difficult conversations demonstrates the leader’s support and commitment to teacher success.

Providing empathy during a feedback conversation means adopting a spirit of humble curiosity. Humility acknowledges the fact that you might not be aware of all details, and curiosity seeks to understand the situation from the teacher’s point of view.

When a leader provides feedback, the danger is that the conversation feels one-sided—and especially if the recipient is not meeting standards. The other person feels as if they are being talked down to rather than engaged with, engendering discouragement rather than leading to growth and success.

Humble curiosity helps ensure that when leaders ask questions, they do so with the intent to understand the situation better rather than simply gather data toward a conclusion. The most effective leaders focus on people and results, simultaneously clarifying expectations and providing empathy during feedback conversations.

Applying the Mindset

Effective feedback conversations are rooted in the right mindset. Principals manifest that mindset by practicing active listening through the application of three critical skills:

- Listening to understand. Focus attention on the other person’s verbal and nonverbal communication. Avoid “listening to respond.” It helps to silence potential distractions such as laptops, cellphones, and smart watches.

- Pausing to process. This gives space for both individuals to think before speaking. Silence allows individuals to consider thoughts and craft thoughtful responses. A pause slows the pace of the conversation slightly to honor cognition and consider difficult feedback.

- Responding intentionally. When responding, leaders should intentionally increase psychological safety so the other person can respond thoughtfully. Two good options are to paraphrase or inquire deeply.

A paraphrased reaction might sound like this: “It seems like you are feeling completely overwhelmed by managing the behavior of your six new students.” The teacher is then free to respond to your summary of events by elaborating on the details of the situation.

Once they feel understood, a leader can inquire deeply. This can include open-ended questions such as, “Are there any teachers you respect who have been able to engage students like those in your third-period class?”

Asking questions during a corrective conversation can feel like an interrogation. Shoring up the other person’s sense of psychological safety increases their cognitive capacity to respond thoughtfully.

Pulling TALK Together

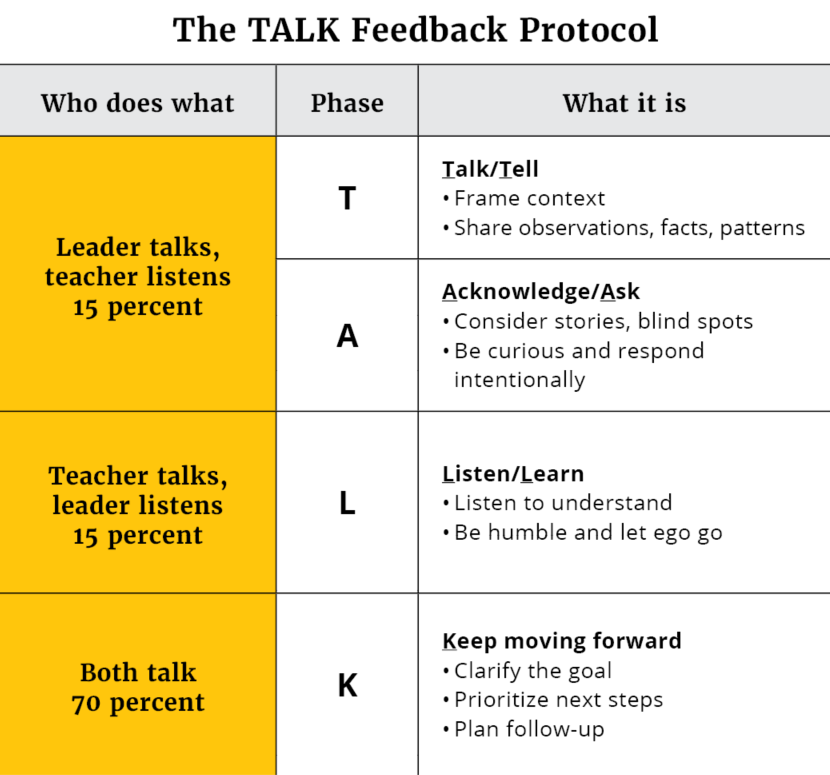

Providing corrective feedback is difficult and sometimes scary, so a clear process can be helpful for a school leader. We constructed the TALK protocol in response to leaders’ desire for support when holding corrective feedback conversations in a respectful and supportive manner.

The protocol is a scaffold that provides clear steps and identifies when the individuals taking part in a conversation talk or listen. The first two phases account for about 15 percent of the time, when the leader talks and the teacher listens. The third phase is also approximately 15 percent of the time, when the teacher talks and the leader listens. The final phase is the bulk of the time, when back-and-forth conversation occurs.

A TALK feedback conversation begins with the Talk and Tell stage, when the leader frames the context and explains the situation from their perspective. It’s an opportunity to clarify your vision of excellence, especially if the teacher is not meeting acceptable standards. It might sound like this:

“Mr. James, I would like to talk to you about what I noticed during the classroom walk-through I did this morning. In the first seven minutes of class, 10 students got out of their seats; John hit Tom in the back of his head on his way back from the pencil sharpener. Eight of the 24 students completed the activity, and only two students raised their hands when asked. This seems to be negatively impacting the ability of your students to learn what you are trying to teach.”

During the second stage—Acknowledge and Ask—the leader demonstrates humble curiosity by acknowledging their own blind spots that might impact how they perceive the situation and ask for the teacher’s point of view. This stage is the shortest—often only a single sentence or two—and might sound like this:

“What I noticed in my most recent walk-through does not meet expectations. I wonder what I’m missing or what I might need to know. How do the observations I just shared align to what you expect?”

As the conversation moves into the third phase—Listen and Learn—the two individuals trade places, so the teacher talks while the leader listens. The goal is to ensure that the leader fully grasps the other person’s perspectives and provides empathy. Being aware of the teacher’s feelings and perspectives helps the leader avoid making decisions based on incomplete assumptions.

Where the first three stages focus on the past, the final stage—Keep Moving Forward—shifts to the future. Next steps are identified, and follow-up (for accountability) is scheduled. Throughout, the leader clarifies excellence and provides empathy, with the goal of outlining what a “win” will look like. When both individuals agree on what that progress looks like, the next steps become obvious. The final part of the conversation with Mr. James might sound like this:

“It sounds like you are aware of the procedures your sixth grade team has for starting class, but you are not sure how to handle the six new students having trouble. Once beginning-of-class procedures are fully implemented, a win might be that all students are able to engage in a bell-ringer activity, follow procedures for sharpening pencils, and get their folders efficiently in seven minutes so you can start a new lesson. Does that align with what you are thinking?”

(Open discussion ensues.)

“Great! Let’s draft an email so you are able to connect with Ms. Jones and see her procedures. I’ll find someone to cover the beginning of your class so you can see them in action, review them with students, and rehearse them with each class. Let’s schedule a time for me to come back and see how it’s going.”

Providing clear, corrective feedback is one of the most important skills leaders use to support teachers in positively impacting student learning. The TALK protocol empowers leaders to provide corrective feedback to teachers while demonstrating respect and support.

Seth N. Brown is director of school improvement for Pitt County (North Carolina) Schools.

Lauren Bowers is professional learning coordinator for Pitt County Schools.

Elizabeth Myers is career pathway specialist for Pitt County Schools.

Thomas R. Feller Jr. is director of school innovation and transformation for Pitt County Schools.