Boost Belonging From the Beginning

Helping students and staff feel seen, valued, and accepted can turn the tide on absenteeism, disengagement, and disciplinary challenges.

Topics: School Culture and Climate, Student Engagement

Across the country, principals are facing a perfect storm. Chronic absenteeism (defined as missing 10 percent or more of school days) is approaching 30 percent. Behavioral incidents are also ticking upward, with rising rates of political- and identity-based bullying and harassment, according to the Southern Poverty Law Center. Student motivation is at an all-time low, with more than one-quarter of students reporting feeling disengaged and less motivated than prior to the COVID-19 pandemic. And educators? They are exhausted, burned out, and leaving the profession in record numbers.

While every school context is different and not everything is gloom-and-doom, one common thread runs through many of the challenges we see today: a breakdown in community, connection, and caring. If we want to meet this moment with courageous solutions within a culture of care, we must treat student belonging not as a buzzword, but as a core strategy for school improvement.

When students feel they don’t belong, they check out or skip school—sometimes quietly through disengagement, and sometimes loudly through defiance, truancy, or disruption. But when students feel as if they belong, everything changes. Belonging increases motivation, facilitates engagement, fuels persistence, and promotes well-being. A strong sense of belonging is a better predictor of student success than many traditional indicators, according to my 2013 research report, “Academic Achievement: A Higher Education Perspective.”

The good news? Belonging is something school leaders can actively cultivate—and in doing so, transform school culture and outcomes for the better.

A Feeling and a Faith

Belonging is not just about fitting in; it’s about feeling seen, valued, and accepted for who you are. More than a fleeting feeling, belonging is also a kind of faith—a belief that you matter and others will take action to meet your needs for safety, respect, connection, and support.

When a child believes “I matter here,” they are far more likely to try, trust, and grow. In the school setting, they are far more likely to attend class/school regularly, put forth effort to excel at tasks, and perform well academically, according to research.

Belonging helps satisfy what psychologists call the “middle need” in typological hierarchy: the need for love and acceptance that comes only after physiological and safety needs are met. And yet in schools today, we often leap straight to academic expectations before laying the foundation for students to feel reliably fed, rested, safe, connected, and cared for.

When that foundation is shaky, everything else is compromised. It’s hard to pay attention in class or pass a test when you’re tired, hungry, or worried, or when you don’t know where you’ll lay your head at night.

The Power of Mattering

Closely tied to belonging is the concept of mattering. Mattering is defined as the sense that we are a significant part of the world around us—that we are noticed, needed, important to others, and making a necessary and valuable contribution.

When students feel they don’t matter, they might disengage, act out, slow down, or give up. But when students feel they do matter, it changes their trajectory. They start to believe that their presence and contributions make a difference, which fuels their motivation, facilitates engagement, nurtures creativity, and boosts belonging.

Principals can help students feel they matter by ensuring that every child is known by name, story, and strength—not just for their test scores, but for their humanity. Acting as instructional leaders, principals can ensure that students see themselves reflected in a curriculum that’s as diverse as they are. They can formulate policies that prohibit bullying, harassment, and fighting (physical or psychological), alongside procedures creating accountability for those who violate such community principles. It starts with the school climate we build and the choices we make every day.

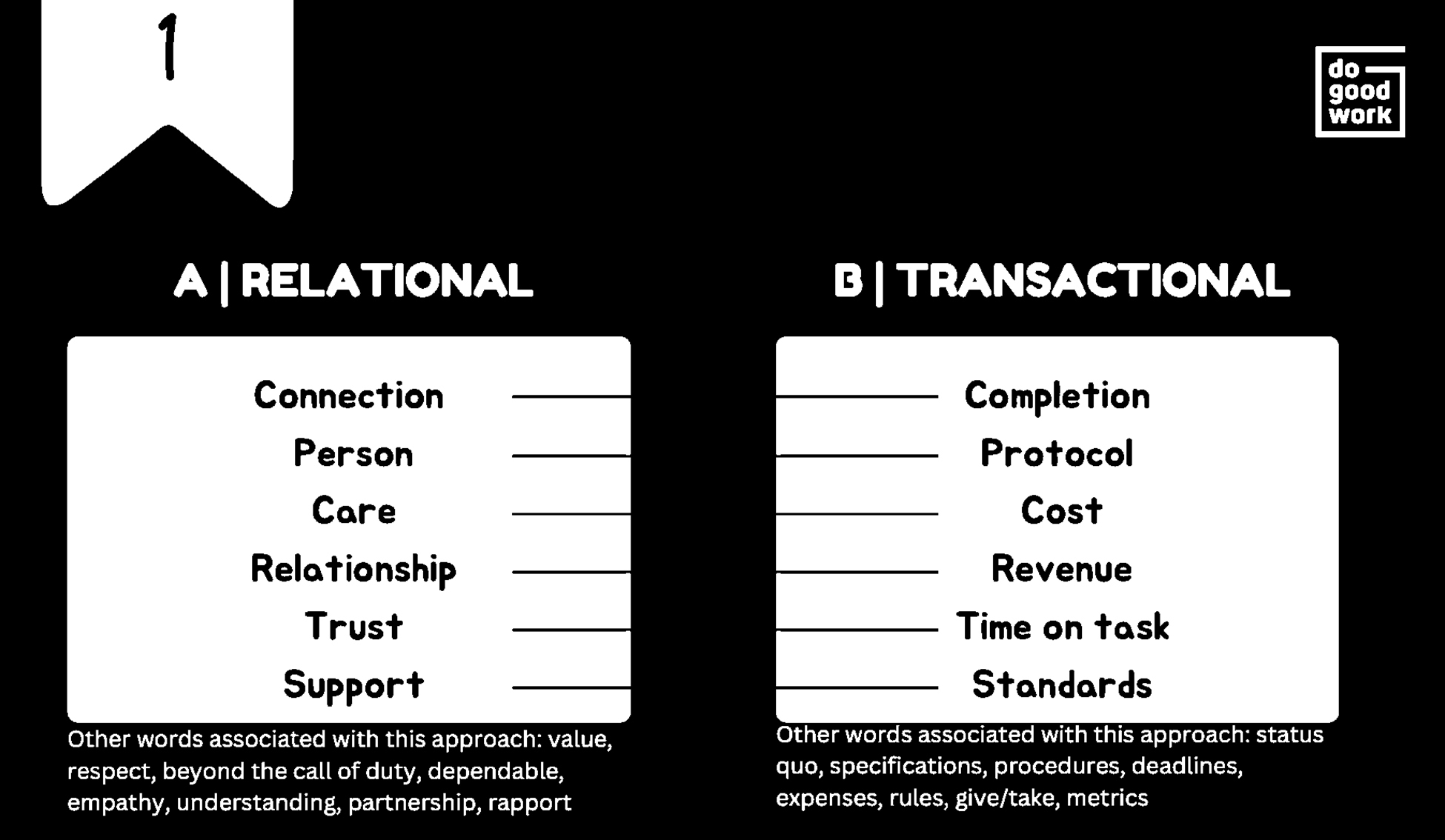

Fig. 1: The differences between relational and transactional approaches

A Strategic Approach to Belonging

Fostering belonging isn’t about one program or a new initiative. It’s a leadership mindset—intentional, strategic, and embedded into the fabric of how a school functions. Here are four key strategies principals can use to create conditions for student belonging:

1. Make belonging evident in your vision. Start with language. Is belonging part of your mission or core values? Do you mention it explicitly in staff meetings, newsletters, or schoolwide goals? Naming it signals to your school community that belonging truly matters and that it’s everyone’s job to boost or build it because everyone wants to belong.

2. Examine data with a belonging lens. Look at chronic absenteeism, office referrals, disciplinary issues, declining grades, and student disengagement not just as maladaptive behaviors or attendance issues, but as signs that students might feel disconnected. Consider adding simple measures of belonging or connectedness to your school climate surveys. Ask students: “Do you feel safe, seen, and supported here?” Use these results when improving existing or designing new programs and initiatives.

3. Prioritize relationships, not just routines. The most powerful belonging interventions aren’t complex. They are relational, not transactional (see Fig. 1). Daily morning meetings, “buddy” classrooms, student check-in circles, friendly interclassroom competitions, and hallway high-fives can go a long way. Systems and schedules should leave room for connection. One middle school principal in Pennsylvania schedules a “relationship reboot” week each quarter—when teachers get additional time to hold one-on-one chats with every student to listen and build rapport.

4. Embed belonging into discipline and support practices. When students misbehave, resist the temptation to simply remove them. Instead, ask what might be behind the behavior. Are they feeling unsafe? Excluded? Unnoticed? One elementary school in Georgia uses restorative practices or circles not just for conflict resolution, but as a daily routine. Circles give students a voice and remind them they are part of a community. Disciplinary referrals in that school have dropped by more than 30 percent.

What Works in Schools

While belonging strategies can look different depending on a school’s needs, here are a few real-world examples of practices that have helped schools boost student success through the power of belonging

and connections:

1. Welcome routines. At a diverse, urban K–5 school in Ohio, every classroom begins the day with a culturally responsive “All Means All” greeting routine. Teachers give students a choice of how they’d like to be greeted—fist bump, wave, smile, song, or kind word. The small ritual builds trust, supports autonomy, and communicates that every child is known and welcomed.

2. Belonging teams. The principal of a pre-K–8 school in California formed a cross-functional “belonging team” of teachers, office staff, a cafeteria worker, and student representatives. Its job? To review cultural climate data and co-design simple strategies to boost student connection, including friendship benches, lunch clubs, readings, and weekly kindness shoutouts. Involving diverse voices ensures that no group is overlooked. The team’s work also led to expansion of cafeteria offerings to respond to growing numbers of students following vegetarian, vegan, or kosher diets.

3. Student voice forums. A middle school in Illinois hosts student “belonging forums” each semester, in which students share—anonymously or in person—their experiences of inclusion and exclusion. The forums are followed by action planning sessions facilitated by an external consultant or speaker. The forums have helped introduce new affinity groups, improved hallway traffic patterns, and more equitable and restorative discipline policies.

Don’t Forget the Adults

Student belonging flourishes best in schools where adults also feel seen and supported. Unfortunately, many educators today feel isolated, undervalued, or burned out. When teachers don’t feel they belong, it’s difficult to create classroom conditions in which students feel they belong.

Principals play a pivotal role in shaping workplace belonging. Start by checking in with staff—not just professionally, but personally. Create space in staff meetings to celebrate small wins and humanize each other. Review your staff recognition practices: Are they equitable? Are all roles honored, from custodian to classroom aide? Find ways to celebrate your newcomers and recent hires, while also showing gratitude to those whose tenures span years or decades.

Structural supports matter, too. Do teachers have a voice in school decisions? Are new staff members mentored, welcomed, and properly onboarded? Can people show up as their authentic selves? If an answer is no, belonging work must begin there. What isn’t provided by the district can be creatively offered at the school level. Pair experienced educators with novice teachers, affirming school values and underlining the fact that it truly “takes a village.”

One solution that’s gaining traction is peer learning communities that focus on staff connection. In one district, a school created “Wellness Wednesdays,” on which teachers gather informally to reflect, vent, and celebrate. The principal offers snacks and protects that time, guaranteeing that there will be no data talk or to-do lists—just community, care, and connection.

I’ve consulted with other schools and districts to facilitate “belonging book clubs” where educators read two chapters of my book each week. We then meet virtually or in person to discuss the content in relation to classroom teaching, student advising, discipline, and so much more.

Belonging Is a Basic Need

When we treat belonging as a soft need or as optional, we miss the opportunity to address some of the most urgent challenges of a school at their roots. Belonging isn’t fluff; it’s foundational.

As principals—especially in pre-K–8 schools where developmental needs are high—we have a unique window to help students internalize the belief that they matter—that they are part of something bigger than themselves. We also have a chance to help our teachers rediscover that same truth.

Belonging won’t solve every problem in education. But it can create conditions in which students and staff are more likely to thrive, grow, and rise to meet the moment. In times of challenge, belonging is not a distraction from the work. It is the work.

Terrell L. Strayhorn is president and CEO of Do Good Work Consulting Group, a professor of education and psychology at Virginia Union University, and director of research at its Center for the Study of HBCUs. He is co-editor of Belonging, a new SAGE journal.