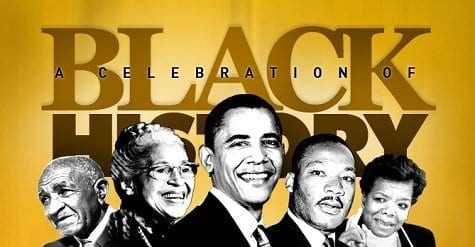

Black History Month and the Elementary School Principal

It’s that time of the year again: Black History Month. In schools across the U.S., this is the time we teach about, read books about, write book reports about and put on performances about famous African Americans. Although there is nothing inherently wrong with this, there is so much more that can and must be done in our recognition of Black History Month; particularly within the context of today’s racial climate across the U.S.

Black History Month started as a week, which occurred the 2nd week in February, 1926 until 1976 when it became a month long recognition. It was founded by Dr. Carter G. Woodson – a scholar, researcher, professor, publisher, author, Dean at Howard University and the 2nd African American to earn a Ph. D. from Harvard University. He founded Negro History Week because he himself discovered a vast amount of Black history that was untold throughout the centuries. He felt that the story of African Americans must be told, documented and disseminated. This went far beyond famous African Americans. This was the story of continental Africans – the ancestors of African American all the way up to the current day, which meant a magnificent story well before enslavement and well after. He felt that this story was not being told which had a profound impact on race relations up until the time Negro History Week was founded and beyond. Much more significantly, he understood that the absence of the study of Black history had a profound impact on the way that African Americans viewed themselves and the world.

Today, when you look at the achievement gap in schools and overall race relations throughout the U.S., there is a need for Black History like never before. In my principalship in urban New Jersey schools, Black History played a crucial role toward creating a climate and culture conducive to my students having a willingness to soar! I used Black History as a launching pad but I did not confine it to February. My students were predominantly economically-disadvantaged African Americans whose lives were replete with a plethora of challenges as a direct result of the circumstances upon which they lived. My task was to make the educational process relevant to their lives so that they ultimately felt empowered to strive for success. The exposure of Black History played a tremendous role toward reaching this objective which enabled us to achieve at much higher levels than schools and districts of equal demographics.

The role of the principal is therefore to ensure that all students; not just the African Americans, are learning the full story of the African American experience. Through lack of exposure, African American children grow up not knowing themselves historically. The same holds true of other races and ethnicities growing up not knowing who their African American peers are historically. To make this shift possible in any given school, the principal’s role cannot be overstated. It is essential. The intentionality of the principal toward making this happen school-wide matters.

Baruti K. Kafele is an educator, author, consultant, and speaker.